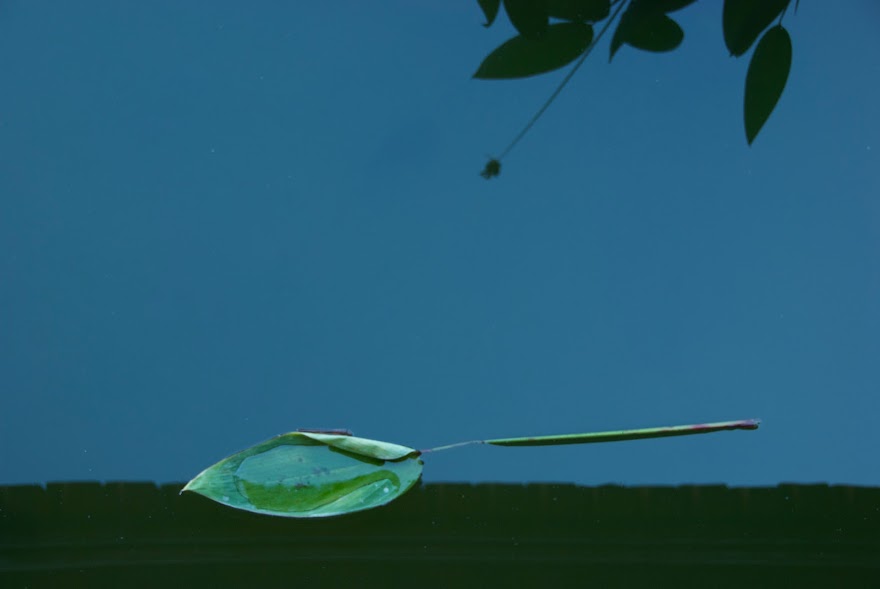

The above photo was taken forty years ago this date. I state it that way because as I write it is still November 1 in San Diego for a few more hours. I am about to sail on what will become my first attempt at Cape Horn. I am thirty-two years old. At sea in nine days I will turn thirty-three. EGREGIOUS had no engine. The mainsail is already set. When I drop that line in my left hand, my life will change from longing to being, a stage which has now lasted improbable decades. I have been fortunate in my health. I have been fortunate in my passions. Sailing GANNET is the mountain climbing equivalent of making a first ascent of a new route, and I doubt that many seventy-two year old mountain climbers are making first ascents.

Today is Sunday and I don’t fly until Tuesday, but, as usual, GANNET is prepared for my departure well in advance. The jib has been lowered and stowed below. Flags are down. Halyards secured. The little sloop tied to the mooring three ways. This is all just as well because rain is due tomorrow.

A young man who runs a yacht care business will board and inspect GANNET once a month in my absence.

Chicago’s weather yesterday made news over much of the world. Never a good sign. High winds and snow. Waves breaking across Lake Shore Drive. I trade summer in a place where I love to be for a Chicago winter without regret. The hardest part of this voyage is not sailing; it is being away from Carol for too long.

———

Adrian Flanagan, a British sailor who made a ‘vertical circumnavigation’, via Cape Horn and then west north of Russia, although he writes that he ‘cargoed’ his boat part of the way, is writing a book about Cape Horn and Cape Horners. A week or so ago he emailed me asking some questions.

Questions

A Background to the voyage

Why did you want to make the voyage which took you round Cape Horn?

I have learned that ‘why?’ is not a good question. People either understand instinctively or they don’t understand at all. Our species has evolved to figure out ‘how’ rather than answer ‘why?’

I believe that societies need most people to maintain stability, and a few to explore physically and mentally.

I consider myself an artist—probably my best known line is: A sailor is an artist whose medium is the wind—and have said that the essential function of the artist is to go to the edge of human experience and send back reports.

The first words of STORM PASSAGE are: I was born for this.

I believe I was; so that’s why.

How did you feel once you had committed to make the voyage?

I committed to the voyage when I was in my teens. I don’t remember any particular feeling other than determination.

Briefly describe your boat

- Technical specs (name of boat, weight, keel arrangement, rig type, LOA, maker, hull material)

The boat which I named EGREGIOUS, using the Latin root of the word meaning ‘out of the herd’, was an Ericson 37, IOR one-tonner, with a fin keel and spade rudder. She may have been the first such boat sailed solo around the Horn. I do not know that as a fact. Perhaps your research will tell.

By design she displaced 16,000 pounds. Mine probably less because I had her built without an engine. She was cutter rigged. 37’ long on deck. Fiberglass. Built by Ericson yachts in California.

- Design attributes/shortcomings for the intended voyage.

Her greatest attribute was that she sailed well. Her greatest shortcoming was a design flaw that ran two bolts through the mast just below the overhead in lieu of tie rods. These sheered off twice.

Also the quality of construction was not of the highest. She was just the best boat I could afford at the time. And despite her flaws did complete a two stop circumnavigation in what was then world record time for a monohull, breaking Chichester’s record by more than three weeks.

At the outset, how confident were you in your boat’s abilities to handle really big weather?

I was the first American to round Cape Horn alone. When I sailed no one in America, including me, knew what it would really be like in the Southern Ocean. I prepared as well as I could and then had the nerve to sail into the unknown.

What was the moment of greatest danger on your voyage?

At sea for almost five months on the passage from San Diego around Cape Horn before finally putting in to Auckland, NZ, EGREGIOUS and I were in Force 12 several times; she was rolled mast into the water three times; caught by Cyclone Colin in the Tasman; had a crack in the hull which required me to bail seven tons of water every twenty-four hours with a bucket; and was in at least 100 knot winds south of Australia.

There was no one moment of greatest danger. There were months of greatest danger.

What was the moment of greatest joy on your voyage?

There were two: rounding the Horn itself and reaching Auckland alive.

B Cape Horn itself

What were your feelings at the prospect of sailing around Cape Horn?

I was eager.

Describe your rounding of Cape Horn – the highs, lows, disasters, fears, joys.

All this can be found in STORM PASSAGE.

In more specific detail, what was the weather like during your rounding of Cape Horn?

I first rounded Cape Horn in December 1975 navigating with a sextant. There was some sleet and snow for the days as I neared the Horn so I kept sailing south until one day I got a single sun sight through clouds that caused me to believe I could turn east. I did and sighted the Diego Ramirez Islands before nightfall. During the night the wind increased to Force 12. The day I passed south of Horn Island without seeing it there were twenty foot breaking waves on each quarter. I tied myself in the cockpit and hand steered at hull speed of eight knots and more under bare poles all day. The servo-rudder from the Aries was in the water and a rooster tail rose from it as from a hydroplane. Around sunset the wind dropped to perhaps fifty knots and I thought the Aries could steer. I went below pleased that the water I was bailing from the bilge into the Atlantic that night had come that morning from the Pacific.

It is a myth that it is always that way.

I sailed around Cape Horn again in 1992 with the woman who was then my wife from New Zealand to Uruguay in RESURGAM, a She 36. The day of the Horn was flat calm in the morning and twenty knots from the northeast in the afternoon. I wrote then, “Some nights Pavarotti has laryngitis. Some days Cape Horn is just another place.”

What kind of shore-side support did you receive during your rounding of Cape Horn – specifically weather advice?

None. No sponsors. No shore team. No PR agent. No way to call for help.

The way I’ve always sailed, though I do have a Yellowbrick on GANNET, the ultralight Moore 24 I am presently sailing, to enable my wife and others to track me.

How did you feel once you were safely past Cape Horn?

I was glad to be passed Cape Horn, but by no means safe. I would still be at sea in the Southern Ocean for three more months and more than 10,000 miles.

What is your perspective today of the voyage you made and specifically your passage round Cape Horn?

I am seventy-two years old—seventy-three next month—and on my sixth circumnavigation, several of which have been pushing the edge of human experience, including my present one. After that first circumnavigation, I set out in an open boat, a stock Drascombe Lugger, which was at least as difficult and as dangerous as my first circumnavigation. I’m proud that I persisted on that first voyage through two earlier failed attempts and through hull and sail damage, that I made a total commitment. At the start of my third, and successful attempt, at Cape Horn, I wrote, “Victory or death.” Now, I’d probably write, “Completion or death,” for I don’t believe we conquer capes or oceans or mountains, we only transit them. But I was going to succeed that third time or die trying; and that is good to have proven about yourself.

C About you

What briefly is your background? (Were you bought up near the sea? Did you learn to sail early? Did your parents sail? etc)

In a jest of the non-existent gods, I was born about as far from the ocean as possible, in Saint Louis, Missouri. No one in my family sailed. I learned from books and taught myself when I bought my first boat at age twenty-five in California.

How do you manage stress?

I have led a very stressful life, both at sea and on land. (See the next answer.) I am used to stress. Occasionally I scream at the sky. But mostly I carry on.

What was the best moment in your life?

I have circumnavigated five times and am now attempting a sixth. I have been married six times to five women, and many other women of great charm, intelligence, beauty, and sensuality of two generations have shared some of their lives with me. I’ve written a good many books, seven of which have been published, and a few poems that I think deserve to be remembered.

There has been too much joy to choose one.

What was the worst moment in your life?

The worst part of my life was my childhood. I don’t dwell on it.

If you are not a professional sailor, what do you do now?

I don’t get paid for sailing, but for writing. I stopped working for other people the day before I left San Diego, California, on my first attempt at Cape Horn in 1974.

Did your experience of Cape Horn affect your attitudes to life in general?

I don’t think so. I think my attitude toward life preceded that first voyage and affected it, rather than the other way around. The only difference was that before the voyage I thought I could do it. Afterwards I knew I could.

------

(The following refers to a comment in Adrian’s cover letter, probably book publisher hype.)

I would like to comment on your statement that Cape Horn is the most feared of the Great Capes. I don’t fear Cape Horn. I rather doubt that you do either, but that is just a guess. I respect the honorable difficulty of sailing around it. But fear? No.

And I am not claiming to have courage. I never have. I do have nerve, which is the willingness after having prepared as well as possible and reduced risk as much as possible, still to attempt to do something where the result is uncertain and may be fatal.