I visited the CRUISING WORLD site recently to see if they had posted any articles of mine I had forgotten and came upon the following, which I had. It was an entry in this journal so many years ago that I think it can bear repetition.

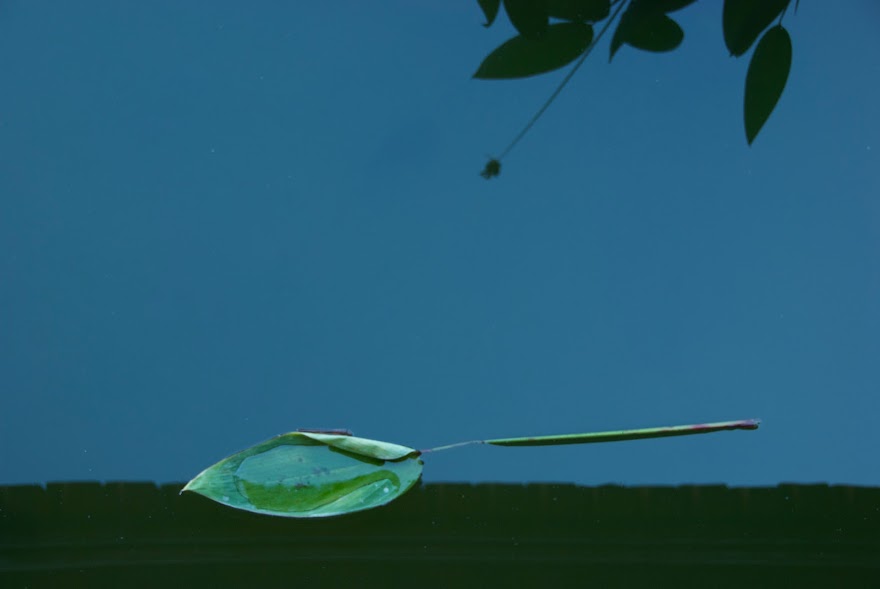

For the record the caption to the photo is wrong. The capsize was halfway between Fiji and what is now Vanuatu, and it occurred in 1980.

A Fraternity of "Fools"

WEBB CHILES IS PART OF AN ELITE GROUP OF "FOOLS" TO CROSS OCEANS (AND SOMETIMES CAPSIZE) IN SMALL, OPEN BOATS. "HOLIDAY STORIES" FROM OUR NOVEMBER 25, 2009, CW RECKONINGS.

By Webb Chiles November 24, 2009

Chidiock Tichborne Webb snapped this shot of his 18-foot Drascombe Lugger, Chidiock Tichborne, after a capsize off Tahiti in the 1970s. Needless to say, he had a waterproof camera.

Now here's a tale to ponder as you recoup from your Thanksgiving turkey and get ready for the holiday season to come. Webb Chiles, back home in Illinois after completing his fifth circumnavigation aboard the Hawke of Tuonela-he left and returned to his mooring in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand-offers up the following from his journal. It's an entry entitled, "Evanston: Fools.”-Ed.

I seldom read sailing books any more; but recently a small boat sailor and

reader of this journal generously sent me a copy of A Voyage of Pleasure:

The Log of Bernard Gilboy's Transpacific Cruise in the Boat, "Pacific" 1882-1883.

I had read this slight volume of only 64 pages several decades ago. Naturally I had

forgotten many details and found interest and pleasure in rereading it, particularly from

the perspective of greater years and experience.

reader of this journal generously sent me a copy of A Voyage of Pleasure:

The Log of Bernard Gilboy's Transpacific Cruise in the Boat, "Pacific" 1882-1883.

I had read this slight volume of only 64 pages several decades ago. Naturally I had

forgotten many details and found interest and pleasure in rereading it, particularly from

the perspective of greater years and experience.

In 1876 Alfred Johnson made the first solo Atlantic crossing in a 20-foot dory, sailing

from Gloucester, Massachusetts, to Abercastle, Wales, in just under two months, with

a brief stop in Nova Scotia. Johnson named his boat, Centennial, and said his voyage

was to commemorate the nation's first hundred years.

from Gloucester, Massachusetts, to Abercastle, Wales, in just under two months, with

a brief stop in Nova Scotia. Johnson named his boat, Centennial, and said his voyage

was to commemorate the nation's first hundred years.

When I completed my first circumnavigation in 1976, a journalist wanted me to claim

that I had done so to honor the Bicentennial. As readers of Storm Passage: Alone

Around Cape Horn know, this was not true and I refused.

Inspired by Johnson, Bernard Gilboy, a professional seaman, had an 18-foot schooner built in San Francisco

specifically for his voyage, at a cost of $400. He considered this the smallest boat

capable of holding provisions for the five months he thought his non-stop passage

would take.

that I had done so to honor the Bicentennial. As readers of Storm Passage: Alone

Around Cape Horn know, this was not true and I refused.

Inspired by Johnson, Bernard Gilboy, a professional seaman, had an 18-foot schooner built in San Francisco

specifically for his voyage, at a cost of $400. He considered this the smallest boat

capable of holding provisions for the five months he thought his non-stop passage

would take.

Her length of 18 feet and beam of 6 feet were almost identical to those of my open boat,

Chidiock Tichborne, but the Pacific had a keel and a draft of 2 feet, 6 inches, as

opposed to unballasted Chidiock Tichborne's 12-inch draft with her centerboard up

and 4 feet with it down.

Chidiock Tichborne, but the Pacific had a keel and a draft of 2 feet, 6 inches, as

opposed to unballasted Chidiock Tichborne's 12-inch draft with her centerboard up

and 4 feet with it down.

Gilboy writes that he somehow squeezed into his craft: "14 ten-gallon casks, filled with

water; 165 pounds of bread, in 15-pound tin cans (air tight); two dozen roast beef in two

and-a-half-pound cans; two dozen roast chicken, in one-pound cans; two dozen roast

salmon, in one-pound cans; two dozen one-pound cans of boneless pigs-feet; two

dozen cans of peaches; two dozen cans of milk; one box containing 25 pounds of

cube sugar; one gross of matches, packed in a half dozen glass jars; one half gallon

of alcohol, in a druggist's glass jar; four cans of nut oil-two and a half gallons in a can;

five-gallon can of kerosene oil; one bar of Castille soap; three pounds of nails; one

wooden pump; 12 feet of half-inch hose, which I used as a siphon to fill the kegs, or

get water out of them; one grains (a fish spear), a hammer, and hatchet; paper, copper

tacks; kerosene oil stove; alcohol pocket stove; two lamps; one pound of paraffin

candles; two compasses, barometer and sextant; patent taff-rail log; double barreled

shot gun, powder and shot, revolver and cartridges; clock and watch; nine knives;

anchor and sea drogue, with about forty fathoms of 1½" rope; some spare marline

amber-line, and marline-spike; navigation books, sheet chart of the South Pacific; an

American flag; clothing necessary for the voyage; two pounds of lard; one pair of

12-foot oars; and an umbrella, which I found very handy when the wind was light and

the sun strong."

water; 165 pounds of bread, in 15-pound tin cans (air tight); two dozen roast beef in two

and-a-half-pound cans; two dozen roast chicken, in one-pound cans; two dozen roast

salmon, in one-pound cans; two dozen one-pound cans of boneless pigs-feet; two

dozen cans of peaches; two dozen cans of milk; one box containing 25 pounds of

cube sugar; one gross of matches, packed in a half dozen glass jars; one half gallon

of alcohol, in a druggist's glass jar; four cans of nut oil-two and a half gallons in a can;

five-gallon can of kerosene oil; one bar of Castille soap; three pounds of nails; one

wooden pump; 12 feet of half-inch hose, which I used as a siphon to fill the kegs, or

get water out of them; one grains (a fish spear), a hammer, and hatchet; paper, copper

tacks; kerosene oil stove; alcohol pocket stove; two lamps; one pound of paraffin

candles; two compasses, barometer and sextant; patent taff-rail log; double barreled

shot gun, powder and shot, revolver and cartridges; clock and watch; nine knives;

anchor and sea drogue, with about forty fathoms of 1½" rope; some spare marline

amber-line, and marline-spike; navigation books, sheet chart of the South Pacific; an

American flag; clothing necessary for the voyage; two pounds of lard; one pair of

12-foot oars; and an umbrella, which I found very handy when the wind was light and

the sun strong."

He needlessly notes that the boat was deep in the water.

And I note one bar of soap for five months.

After obtaining his customs clearance for what was listed as "a voyage of pleasure,"

Bernard Gilboy called, "All aboard for Australia," and shoved off. He made very good

time his first week, covering 510 miles, particularly considering that he stopped to

sleep, either heaving to or letting the small schooner swing to a sea anchor drogue.

Bernard Gilboy called, "All aboard for Australia," and shoved off. He made very good

time his first week, covering 510 miles, particularly considering that he stopped to

sleep, either heaving to or letting the small schooner swing to a sea anchor drogue.

However progress came to a stop when he reached 9 degrees North, and he made

only 237 miles in the next 29 days. Finally at 5 degrees North, he started moving again.

In describing conditions, Gilboy often uses charming expressions with which I was not

familiar, such as "baffling wind" and "mizzling rain."

only 237 miles in the next 29 days. Finally at 5 degrees North, he started moving again.

In describing conditions, Gilboy often uses charming expressions with which I was not

familiar, such as "baffling wind" and "mizzling rain."

Ninety days out of San Francisco he was near Tahiti.

Although San Francisco is 500 miles north of San Diego, in Chidiock Tichborne I was

within six miles of Tahiti in 39 sailing days. I was, of course, not carrying provisions for

five months.

within six miles of Tahiti in 39 sailing days. I was, of course, not carrying provisions for

five months.

Disaster struck with the passing of a single wave, which capsized the Pacific south of

Fiji on December 12, his 116th at sea, only a few hundred miles southeast of where

another single wave flipped Chidiock Tichborne 98 years later.

Fiji on December 12, his 116th at sea, only a few hundred miles southeast of where

another single wave flipped Chidiock Tichborne 98 years later.

Gilboy lost a mast, the rudder, his sextant and compass, and almost all of his provisions.

Steering with an oar until he made a seamanlike substitute rudder with a jury rig, he

struggled on, starving, until on January 29, he was seen and picked up, boat and all,

by a passing schooner. At the time he was 200 miles off the Australian Queensland

coast.

Steering with an oar until he made a seamanlike substitute rudder with a jury rig, he

struggled on, starving, until on January 29, he was seen and picked up, boat and all,

by a passing schooner. At the time he was 200 miles off the Australian Queensland

coast.

Gilboy's almost successful attempt to make the first solo voyage across the Pacific

Ocean surely ranks among the greatest almost unknown voyages.

Ocean surely ranks among the greatest almost unknown voyages.

When late in life, Alfred Johnson was asked why he had sailed across the Atlantic alone,

he replied, "I made that trip because I was a damned fool, just as they said I was."

he replied, "I made that trip because I was a damned fool, just as they said I was."

In the March 24, 1883, issue of the San Francisco Daily Alta California newspaper

appeared: "The dory Pacific is reported as arrived safely at Australia. Her only occupant

gives a thrilling account of his perilous trip. He arrived, as above, and the fools are not

all dead yet."

appeared: "The dory Pacific is reported as arrived safely at Australia. Her only occupant

gives a thrilling account of his perilous trip. He arrived, as above, and the fools are not

all dead yet."

To which I offer the very last words in Storm Passage: "The fool smiles and sails on."

————

I have spent much of my adult life outside the United States. Now I am away only

six or seven months at a time. In the past I was often gone for years.

six or seven months at a time. In the past I was often gone for years.

Each time I return I find some new young person I have never heard of is famous

and presumably wealthy.

and presumably wealthy.

When I returned to Evanston last month I was particularly struck by how strident is

television.

television.

It was not just the politicians, but everyone, from the talking heads who speak rapidly

what poses as news in tones of near hysteria, pausing only to emphasize, as they

must be taught in school because they all do it, words that heighten fear; to almost all

advertising, which essentially is exaggerated lies; to excessively analyzing sports

commentators. Nature may abhor a vacuum. Television and modern America abhors

silence.

what poses as news in tones of near hysteria, pausing only to emphasize, as they

must be taught in school because they all do it, words that heighten fear; to almost all

advertising, which essentially is exaggerated lies; to excessively analyzing sports

commentators. Nature may abhor a vacuum. Television and modern America abhors

silence.

I can turn all this off and I usually do. I watch almost no news on television, except

local, and I often watch sports with the volume muted while listening to music on

headphones.

local, and I often watch sports with the volume muted while listening to music on

headphones.

During last Saturday’s football games there were two commercials that were

exceptions to the advertising rule: one by Apple, one by GE, both advocating being

kind to those who are different, which of course is all of us, rather than shrilly pitching

their own products.

exceptions to the advertising rule: one by Apple, one by GE, both advocating being

kind to those who are different, which of course is all of us, rather than shrilly pitching

their own products.

I am enjoying being with Carol, but I long for the silence of the sea.

————

From James comes a link to an article that seems to confirm my subjective

observation that just forward of a beam reach is the fastest point of sail, though on

GANNET I would rather have the wind just aft.

observation that just forward of a beam reach is the fastest point of sail, though on

GANNET I would rather have the wind just aft.

I thank him.

————

And from Tim comes a link to a YouTube video of “The Solent”, an early

composition by Ralph Vaughan Williams, accompanied by some lovely paintings.

An antidote to the strident.

composition by Ralph Vaughan Williams, accompanied by some lovely paintings.

An antidote to the strident.

I thank him and wish you serenity.