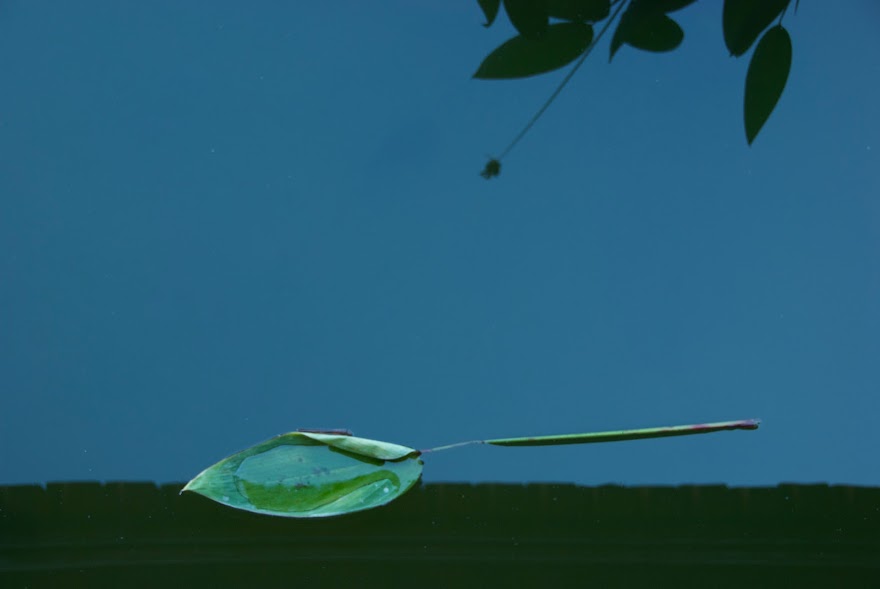

Steve Earley took the above beautiful photo, which he has captioned ‘Before Sunrise’, a few mornings ago during his ongoing fall cruise. Steve and I have mutual permission to repost anything from either of our sites. I thank him for that.

Steve retired earlier this year from his long career as a newspaper photographer. He enjoyed his work and and initially had what I observe is a common unease at the transition. ‘Observe’ because either I retired the day I graduated from college as my grandmother liked to say or I will never retire at all. I told Steve, “You are not retired. You are free.” And on this fall cruise with no date he has to be back at work he is sensing that. The greatest wealth is time. That we have so little is our dignity, if we make something of it.

You can follow Steve’s cruise here:

http://logofspartina.blogspot.com/

https://maps.findmespot.com/s/XDZW#history/assets

I just finished reading THE SECRET LIFE OF GROCERIES and I’m giving up food.

I learned of the book from a front page review in the NY TIMES.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/08/books/review/the-secret-life-of-groceries-benjamin-lorr.html

The book is fascinating and I don’t even care much about food. I like good food when I can get it, but obviously can live indefinitely on cans and freeze dried.

THE SECRET LIFE is not muckraking in the Upton Sinclair style, but reveals the details and hidden side of the food supply chain from fisherman and slaughter house, to truck driver, entrepreneur, worker at the fish counter at Whole Foods. People and things that most of us, including me, take for granted and never consider.

I came away from the book impressed by the attention to detail, the complications, the competitiveness, and particularly to the squeeze of those on the lowest levels of the supply chain, some of whom are victims not just of wage slavery but real slavery.

A couple of statistics. Once 90% of the US population was engaged in producing food. Now only 3%. And as you can read in the review, the average American spends 2% of their life in supermarkets.

Assuming you eat, you will find this book of interest.

This morning at Sailing Anarchy I learned that a new 33’ Moore is going into production.

She will certainly be fast.

I notice that there is no mention of price, but whatever it is, sorry, Ron, but I won’t be buying one.

I’m sticking with GANNET on whom during the past few weeks I have once again spent more than I originally paid for her.

I came across a troubling poem the other day. I will let it speak for itself. That is what poems do.

He Sits Down on the Floor of a School for the Retarded

I sit down on the floor of a school for the retarded,

a writer of magazine articles accompanying a band

that was met at the door by a child in a man’s body

who asked them, “Are you the surprise they promised us?”

It’s Ryan’s Fancy, Dermot on guitar,

Fergus on banjo, Denis on penny-whistle.

In the eyes of this audience, they’re everybody

who has ever appeared on TV. I’ve been telling lies

to a boy who cried because his favorite detective

hadn’t come with us; I said he had sent his love

and, no, I didn’t think he’d mind if I signed his name

to a scrap of paper: when the boy took it, he said,

“Nobody will ever get this away from me,”

in the voice, more hopeless than defiant,

of one accustomed to finding that his hiding places

have been discovered, used to having objects snatched

out of his hands. Weeks from now I’ll send him

another autograph, this one genuine

in the sense of having been signed by somebody

on the same payroll as the star.

Then I’ll feel less ashamed. Now everyone is singing,

“Old MacDonald had a farm,” and I don’t know what to do

about the young woman (I call her a woman

because she’s twenty-five at least, but think of her

as a little girl, she plays the part so well,

having known no other), about the young woman who

sits down beside me and, as if it were the most natural

thing in the world, rests her head on my shoulder.

It’s nine o’clock in the morning, not an hour for music.

And, at the best of times, I’m uncomfortable

in situations where I’m ignorant

of the accepted etiquette: it’s one thing

to jump a fence, quite another thing to blunder

into one in the dark. I look around me

for a teacher to whom to smile out my distress.

They’re all busy elsewhere, “Hold me,” she whispers. “Hold me.”

I put my arm around her. “Hold me tighter.”

I do, and she snuggles closer. I half-expect

someone in authority to grab her

of me: I can imagine this being remembered

for ever as the time the sex-crazed writer

publicly fondled the poor retarded girl.

“Hold me,” she says again. What does it matter

what anybody thinks? I put my arm around her,

rest my chin in her hair, thinking of children,

real children, and of how they say it, “Hold me,”

and of a patient in a geriatric ward

I once heard crying out to his mother, dead

for half a century, “I’m frightened! Hold me!”

and of a boy-soldier screaming it on the beach

at Dieppe, of Nelson in Hardy’s arms,

of Frieda gripping Lawrence’s ankle

until he sailed off in his Ship of Death.

It’s what we all want, in the end,

to be held, merely to be held,

to be kissed (not necessarily with the lips,

for every touching is a kind of kiss.)

Yet, it’s what we all want, in the end,

not to be worshiped, not to be admired,

not to be famous, not to be feared,

not even to be loved, but simply to be held.

She hugs me now, this retarded woman, and I hug her.

We are brother and sister, father and daughter,

mother and son, husband and wife.

We are lovers. We are two human beings

huddled together for a little while by the fire

in the Ice Age, two thousand years ago.

—Alden Nowlan

I am virtuous. No one else will say so, so I must.

I did my full workout yesterday for the first time in eight weeks. I can do the workout on GANNET’s foredeck, but for whatever reasons this time in San Diego I didn’t.

I managed to do one foot push-ups, keeping my weight on my left foot while my right barely touched the floor. I only went to my age plus one, which I will have to do in a couple of months anyway. I’ll do weights today.

Thanks for the wonderful poem.

ReplyDelete